Chloe’s Thoughts, Essays

2.25.22

“Beauty and Reality are Identical: On the Fixed Star Vega”

“Beauty and Reality are Identical: On the Fixed Star Vega”

Divine Illusion

The history of the lyre begins with deception. According to myth, Hermes, son of Zeus, created the instrument not long after his birth. Though just a newborn, the messenger god slips out of his swaddling and happens upon a herd of cows owned by Apollo, god of the sun. He manages to steal them all but is discovered when local satyrs hear him play his new invention, which he fashioned from a tortoise shell and cow guts. Though he tries to deny his theft, he eventually confesses to slaughtering two of Apollo’s flock but ends up getting to keep the rest; Apollo, a deity of the arts, is enchanted by the sound Hermes’s new invention can make and trades his herd to keep it. Zeus, Hermes’s father, tells him to to stop telling lies. Though he promises to “never tell lies,” he “cannot promise to tell you the whole truth”.

“‘That would not be expected of you,’ said Zeus, with a smile,” Robert Graves is sure to relay.

And so begins our exploration of Vega, the primary star in the Lyra constellation. Though it has been given many images and titles over the years, it has always been tied with musical instruments, usually the harp, or in the case of Ancient Greece, the lyre. Rather than connecting it with Hermes, they connect Vega with the lyre of Orpheus, son of Apollo and thus a direct beneficiary of Hermes’s trickery. After receiving the instrument from his father, “the Muses taught him its use, so that he not only enchanted wild beasts, but made the trees and rocks move from their places to follow the sound of his music”. To have a natal connection to Vega is said to imbue the native with artistic ability, specifically in music and acting.

Here we have another view of deception: the ability of art to alter our relationship to reality, for better or for worse.

Art in Ancient Greece

One of the places where these sorts of half-truths is not just allowed but accepted, of course, is in the world of art. But in Ancient Greece, Plato questioned art’s ability to blur the lines of truth. Because “Poetry, drama, music, painting, dance, all stir up our emotions,” the philosopher believed they should be heavily censored, for fear of the common people mistaking a fabrication of the Truth for the real thing. Though he acknowledges the potential for art to shape human character for the good (even including music and dance in the school curriculum in his Republic), he spends plenty of time worrying about the deleterious effects of uncensored art on the general population. Music played simply for pleasure was dismissed as “irrational,” especially considering the lofty potentials music presents us.

Music was especially emphasized for its ability to bring one either into harmony or disharmony with the proper movement of the human soul. This connection comes from “[t]he idea that there are revolutions in the souls that are similar to those of the celestial bodies”. Thus music was “seen as an expression of this cosmic attunement and concord”. Music was seen as “an ally against the disharmony that has come into the revolution of the soul, to bring it into order and consonance (sumphonia) with itself”. The truth that art could extend to us, then, was not the bland truth of a purely objective, materialist world, but a transcendent truth handed down to us from the heavenly spheres embedded into our everyday reality. As Plato derides anything that induces men “to regard the reality which falls under our senses as the only reality,” music was seen as especially virtuous for its connection with the movements of the heavens.

Here we learn a few interesting points for Vega natives: To be given the gift of creativity is to be given great power. You can enchant others, bid them to follow you, and influence the shape of their soul. Art can act not merely as a mirror to one’s psyche but can act as a portal to spiritual truths or a connection to the divine. But, on the other side, Vega can also lead them away from reality and fabricate illusions for one’s own gain. A Vega native must be aware if their art or expression are coming from a place of virtue or connection to spirit rather than a mere tool for personal gain/of egoic origin.

Defying Death

The most well-known of lyre players, and an exemplar of this dictum, was Orpheus, who, according to Robert Graves’s “Myths,” was “the most famous poet and musician who ever lived”. The divine relation between the heavens and music are apparent through the story of Orpheus. After being given his first lyre by Apollo and being taught how to play by the muses, Orpheus was said to enchant wild beasts and make ”the trees and rocks move from their places to follow the sound of his music”. Through the skill and blessing of the player, the lyre acts as a conduit for divine energy, drawing all beings to it.

The lyre even helped Orpheus defy death. After his love, Eurydice, dies of a snake bite, he travels to the underworld and:

Guided by the sound of the lyre, Eurydice makes her slow ascent back to the world of the living. But just as they reach sunlight, Orpheus turns to look at her, breaking the one condition of her safe return.

Orpheus is heartbroken, of course, and ends up dying at the hands of the Bacchae, crazed followers of Dionysus, God of wine and reverie. Where his remains end up, however, tell us why his descent was doomed to fail.

The Head and the Harp

According to Robert Graves, while Orpheus’s lyre ended up in the sanctuary of Apollo, his severed head was interred in the sanctuary of Dionysus. These two gods are often paired with each other as a demonstration of opposites; Apollo represents the clear light of intellect, Dionysus the ecstatic wildness of the senses. It is clear, then, that the instrument itself, divinely created and attuned, holds the power of the gods, as well as the eternal order and rhythm of the heavens that Plato so praised. But it is only in the hands of a human that beautiful music can be plucked from its strings. This fact also subjects the instrument to human passion and irrationality, the very things that make Plato so derisive of art. But, as the lyre cannot play itself, we also rely on the subjective human body to bring its enchantments to life.

To play the lyre, in other words, one must balance the roles of divine vessel, expounding the pre-existing perfection of the heavenly spheres, while also using one’s tricky, irrational passions to bring about the enchanting effect.

That’s the issue with Vega; sometimes, you’re not quite sure if something is real or an illusion. But there must a remembrance, a reverence for the source of the music. To engage with Vega well, one must remember the source of the music lies beyond one’s mind, not mistaking the vessel for its contents.

Vega in Motion

One Vega native that demonstrates this tension between the divine and the earthly is Simone Weil, 20th French mystic. Known for her religious writings and political activism during World War II, much of her writing grapples with the necessary mediation of the divine through the human body and mind.

In “Gravity and Grace,” a collection of her writings which features a whole section entitled “Beauty”, she tells us that ““beauty and reality are identical,” calling to mind the fact that, true gnosis of the god or Truth, is an aesthetically and emotionally rich event, one that can fill us with the feelings and reveries that Plato so feared. A spiritual appreciation of beauty is enough to mark a Vega native. But Weil also cautioned against mistaking the beauty as the only truth. She compares beauty to “a fruit which we look at without trying to seize it” and also penned this adage:

“A very beautiful woman who looks at her reflection in the mirror can very well believe that she is that. An ugly woman knows that she is not that.”

Here we have two facts: One, that the visage we see reflected back to us is not truly us. For Weil, our true self lies with God, passes through God, is god.

Secondly, the more charming the illusion, the more likely we are to believe it. And that is the tight rope that Vega natives must balance; on the one hand, to be incarnated is to be surrounded by beauty, as each thing is a reflection of the divine origin. On the other, they must avoid illusions or mistaking the form for the substance.

Vega, like any gift, brings with it a moral responsibility to truth as you see it; you may dress it up in music, words, dance. With any luck, you can see the divine truth underneath the facade and perhaps even bring back the dead.

But don’t for a moment think these powers come from you alone. Trust in god and where that message is going, even if you can’t see it, lest you turn your head too soon and see everything you love vanish again.

Sources:

The history of the lyre begins with deception. According to myth, Hermes, son of Zeus, created the instrument not long after his birth. Though just a newborn, the messenger god slips out of his swaddling and happens upon a herd of cows owned by Apollo, god of the sun. He manages to steal them all but is discovered when local satyrs hear him play his new invention, which he fashioned from a tortoise shell and cow guts. Though he tries to deny his theft, he eventually confesses to slaughtering two of Apollo’s flock but ends up getting to keep the rest; Apollo, a deity of the arts, is enchanted by the sound Hermes’s new invention can make and trades his herd to keep it. Zeus, Hermes’s father, tells him to to stop telling lies. Though he promises to “never tell lies,” he “cannot promise to tell you the whole truth”.

“‘That would not be expected of you,’ said Zeus, with a smile,” Robert Graves is sure to relay.

And so begins our exploration of Vega, the primary star in the Lyra constellation. Though it has been given many images and titles over the years, it has always been tied with musical instruments, usually the harp, or in the case of Ancient Greece, the lyre. Rather than connecting it with Hermes, they connect Vega with the lyre of Orpheus, son of Apollo and thus a direct beneficiary of Hermes’s trickery. After receiving the instrument from his father, “the Muses taught him its use, so that he not only enchanted wild beasts, but made the trees and rocks move from their places to follow the sound of his music”. To have a natal connection to Vega is said to imbue the native with artistic ability, specifically in music and acting.

Here we have another view of deception: the ability of art to alter our relationship to reality, for better or for worse.

Art in Ancient Greece

One of the places where these sorts of half-truths is not just allowed but accepted, of course, is in the world of art. But in Ancient Greece, Plato questioned art’s ability to blur the lines of truth. Because “Poetry, drama, music, painting, dance, all stir up our emotions,” the philosopher believed they should be heavily censored, for fear of the common people mistaking a fabrication of the Truth for the real thing. Though he acknowledges the potential for art to shape human character for the good (even including music and dance in the school curriculum in his Republic), he spends plenty of time worrying about the deleterious effects of uncensored art on the general population. Music played simply for pleasure was dismissed as “irrational,” especially considering the lofty potentials music presents us.

Music was especially emphasized for its ability to bring one either into harmony or disharmony with the proper movement of the human soul. This connection comes from “[t]he idea that there are revolutions in the souls that are similar to those of the celestial bodies”. Thus music was “seen as an expression of this cosmic attunement and concord”. Music was seen as “an ally against the disharmony that has come into the revolution of the soul, to bring it into order and consonance (sumphonia) with itself”. The truth that art could extend to us, then, was not the bland truth of a purely objective, materialist world, but a transcendent truth handed down to us from the heavenly spheres embedded into our everyday reality. As Plato derides anything that induces men “to regard the reality which falls under our senses as the only reality,” music was seen as especially virtuous for its connection with the movements of the heavens.

Here we learn a few interesting points for Vega natives: To be given the gift of creativity is to be given great power. You can enchant others, bid them to follow you, and influence the shape of their soul. Art can act not merely as a mirror to one’s psyche but can act as a portal to spiritual truths or a connection to the divine. But, on the other side, Vega can also lead them away from reality and fabricate illusions for one’s own gain. A Vega native must be aware if their art or expression are coming from a place of virtue or connection to spirit rather than a mere tool for personal gain/of egoic origin.

Defying Death

The most well-known of lyre players, and an exemplar of this dictum, was Orpheus, who, according to Robert Graves’s “Myths,” was “the most famous poet and musician who ever lived”. The divine relation between the heavens and music are apparent through the story of Orpheus. After being given his first lyre by Apollo and being taught how to play by the muses, Orpheus was said to enchant wild beasts and make ”the trees and rocks move from their places to follow the sound of his music”. Through the skill and blessing of the player, the lyre acts as a conduit for divine energy, drawing all beings to it.

The lyre even helped Orpheus defy death. After his love, Eurydice, dies of a snake bite, he travels to the underworld and:

on his arrival, not only charmed the ferryman Charon, the Dog Cerberus, and the three Judges of the Dead with his plaintive music, but temporarily suspended the tortures of the damned; and so far soothed the savage heart of Hades that he won leave to restore Eurydice to the upper world”.

Guided by the sound of the lyre, Eurydice makes her slow ascent back to the world of the living. But just as they reach sunlight, Orpheus turns to look at her, breaking the one condition of her safe return.

Orpheus is heartbroken, of course, and ends up dying at the hands of the Bacchae, crazed followers of Dionysus, God of wine and reverie. Where his remains end up, however, tell us why his descent was doomed to fail.

The Head and the Harp

According to Robert Graves, while Orpheus’s lyre ended up in the sanctuary of Apollo, his severed head was interred in the sanctuary of Dionysus. These two gods are often paired with each other as a demonstration of opposites; Apollo represents the clear light of intellect, Dionysus the ecstatic wildness of the senses. It is clear, then, that the instrument itself, divinely created and attuned, holds the power of the gods, as well as the eternal order and rhythm of the heavens that Plato so praised. But it is only in the hands of a human that beautiful music can be plucked from its strings. This fact also subjects the instrument to human passion and irrationality, the very things that make Plato so derisive of art. But, as the lyre cannot play itself, we also rely on the subjective human body to bring its enchantments to life.

To play the lyre, in other words, one must balance the roles of divine vessel, expounding the pre-existing perfection of the heavenly spheres, while also using one’s tricky, irrational passions to bring about the enchanting effect.

That’s the issue with Vega; sometimes, you’re not quite sure if something is real or an illusion. But there must a remembrance, a reverence for the source of the music. To engage with Vega well, one must remember the source of the music lies beyond one’s mind, not mistaking the vessel for its contents.

Vega in Motion

One Vega native that demonstrates this tension between the divine and the earthly is Simone Weil, 20th French mystic. Known for her religious writings and political activism during World War II, much of her writing grapples with the necessary mediation of the divine through the human body and mind.

In “Gravity and Grace,” a collection of her writings which features a whole section entitled “Beauty”, she tells us that ““beauty and reality are identical,” calling to mind the fact that, true gnosis of the god or Truth, is an aesthetically and emotionally rich event, one that can fill us with the feelings and reveries that Plato so feared. A spiritual appreciation of beauty is enough to mark a Vega native. But Weil also cautioned against mistaking the beauty as the only truth. She compares beauty to “a fruit which we look at without trying to seize it” and also penned this adage:

“A very beautiful woman who looks at her reflection in the mirror can very well believe that she is that. An ugly woman knows that she is not that.”

Here we have two facts: One, that the visage we see reflected back to us is not truly us. For Weil, our true self lies with God, passes through God, is god.

Secondly, the more charming the illusion, the more likely we are to believe it. And that is the tight rope that Vega natives must balance; on the one hand, to be incarnated is to be surrounded by beauty, as each thing is a reflection of the divine origin. On the other, they must avoid illusions or mistaking the form for the substance.

Vega, like any gift, brings with it a moral responsibility to truth as you see it; you may dress it up in music, words, dance. With any luck, you can see the divine truth underneath the facade and perhaps even bring back the dead.

But don’t for a moment think these powers come from you alone. Trust in god and where that message is going, even if you can’t see it, lest you turn your head too soon and see everything you love vanish again.

Sources:

- “Gravity and Grace,” Simone Weil

- “The Greek Myths” by Robert Graves

- “The Book of Symbols,” Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbols (ARAS)

- “Plato’s attitude to poetry and the fine arts, and the origins of aesthetics,” Walter. G. Leszl

2.18.22

“Pregnant with Freedom: On the Fixed Star Capella”

“Pregnant with Freedom: On the Fixed Star Capella”

What is the felt experience of freedom? And from where does it spring? How can freedom fit into the personal and how can we nurture it? These are questions that Capella, fixed star of the Charioteer, attempts to answer for us. Beginning his life as the crook of the great shepherd in Ancient Babylon, the Greeks depicted “Auriga,” the constellation in which Capella is placed, as a man carrying a whip and riding a chariot. The charioteer still carries his pastoral roots in the form of a goat nestled into his left shoulder, which makes sense as a deeper shade to this freedom-loving star. What is the pastoral but a fantasy of the wild tamed into usefulness? And isn’t that what a horse is too?

Wild Horses

Though originally wild, wildy beautiful creatures, “We tamed them,” The Book of Symbols tells us. But through the harnessing of their feral power, we attained greater speed and efficiency: “Our struggle for freedom has been won through the freedom they have sacrificed for us in exchange for a powerful mutual bond and benefit”. Freedom lies at the edge of our comfort, in other words. By harnessing the raw power of the horse we can surpass that edge. Beyond their physical stamina, horses have long been used to symbolize spiritual enlightenment. “If life is to be lived as a fully embodied spiritual adventure,” one must tune into the “pulsing libido” and “raw powers” of the horse. By staying in touch with our animal nature we resist full integration into the taming nature of civilization.

Capella and Diana

But the star’s history also connects Capella to the maternal. Auriga is also depicts the she-goat who nursed Zeus when he was a child, therefore exalting her to the heavens. The nurturing quality of this star is enhanced by its use in Ancient Greece. This star served as an orientation point for the temple at Eleusis dedicated to Diana, Goddess of the Moon.

Though the moon has long been associated with the body and its care, it would be specious to reduce Diana to a nurturing goddess. As the goddess of the hunt, she was able to roam freely and explore the wilderness. As a virgin goddess, her ability to move as she pleased was assured. She was not like Selene, the goddess of the full moon, or Hecate the mystic crone of the dark moon, but shows the moon in her waxing phase, incarnating into reality and embodying the heavens as something quick-footed, and powerful, yet elusive. Get too close to her, as Actaeon did, and risk being transformed into a wild animal, losing all civilizing traes. Like a horse, Artemis is not a violent being but has the power to defend her boundaries if crossed.

…

This duality is embodied in the general descriptions of this star. Brady associates Capella with a “nurturing but free-spirited flavor” and links it with the “pursuit of freedom in a non-aggressive way”. Diana does not wish to impede on the freedom of others to maintain her own; she was known for hunting with female attendants, proving her lack of restraint doesn’t impede her ability to make connections. But her love doesn’t come with caveats or obligations. “I will try hard to hold onto you with open arms,” Fiona Apple vows in “Daredevil” and Capella holds the same vibe. To be a parent is to take care of a being who will someday not need you. To love another is to continually show up and witness their shifts and changes even if they differ from what you expected.

…

How funny; I am relistening to “Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea,” ostensibly PJ Harvey’s most straightforward, hard rock, “in love,” album and I am stuck on the song that is none of that. Starting with slow piano and strings that drift through a lazy river, in bleeds Harvey’s voice, expounding a dream she had: “Horses in my dreams/Like waves, like the sea”. We don’t know if she saw them like waves in the dream or whether this is just a metaphor she added after the fact. If she really saw horses in her dreams, they must have been moving in slow motion. Though there are orchestral swells to the song, it keeps its legato, meandering tone throughout. Yet there is liberation within this molasses flow. “They pull out of here

They pull, they are free,” she tell us. In the chorus, she mimics them: “I have pulled myself clear,” she repeats like a somber chant though the relief in her voice is evident.

This song seems to depict a certain kind of freedom: one that isn’t exultant or forced like a war chant or a breaking of chains. This freedom flows in like a wave, slowly dissolving manacles or pulling you into a larger flow, one where freedom is the air you breathe. It presents freedom not as a place without work or strictures, but one where your movement is joined with something larger than you. She doesn’t explain how she pulled clear, but her feeling of doing so is undeniable, unable to be taken away.

Harvey spoke of the difficulty of writing this song because of its intimacy: “When I was writing [“Horses in my Dreams”], it was a very difficult, emotional thing to go through doing, because it is so close to me, it is a very personal song that one. And it remains so, really”.

…

Nurturing Freedom

In her Orphic Hymn, Artemis is called “Dictynna,” meaning “Lady of the Nets”. This star is not simply a star of the horse, but of the man who places a bridle atop it. We can even see Artemis’s association with childbirth as a gesture towards tethering.

To know freedom one must know chains— their weight and the lightness that comes with them falling off. But this very quality means the freedom is incomplete— relationships require our own taming, after all. A noble sacrifice, not to be weighed lightly.

Janis Joplin had Capella as her heliacal setting star. Brady sees this combination as a “struggle with a love of freedom in conflict with the need for personal commitments”— the inability to cut all ties whether they be bridle or net.

Joplin was always an outcast; she was considered unattractive in her small Texas hometown and was ostracized for her love of blues and soul music, “black” genres. She dropped out of college and moved to San Francisco to pursue music. She was known for her hard drinking and ultimately left the band that she started with to pursue a solo career. She had relationships with many men and women throughout her life and once broke a bottle over Jim Morrison’s head. But she also kept regular correspondence with her parents, even writing to them ““Weak as it is,” she wrote, “I apologize for being just so plain bad in the family,” for leaving home.

One of Janis Joplin’s most famous songs speaks to this tension. Perhaps the most famous line from “Me and Bobby McGee” is this one: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose”. Kris Kristofferson, who wrote the song, said this on inspiration for it: “The two-edged sword that freedom is. He was free when he left the girl, but it destroyed him”.

How can freedom maintain its connections? This is what Capella asks of us.

Capella natives will spend their lives trying to answer this question.

Wild Horses

Though originally wild, wildy beautiful creatures, “We tamed them,” The Book of Symbols tells us. But through the harnessing of their feral power, we attained greater speed and efficiency: “Our struggle for freedom has been won through the freedom they have sacrificed for us in exchange for a powerful mutual bond and benefit”. Freedom lies at the edge of our comfort, in other words. By harnessing the raw power of the horse we can surpass that edge. Beyond their physical stamina, horses have long been used to symbolize spiritual enlightenment. “If life is to be lived as a fully embodied spiritual adventure,” one must tune into the “pulsing libido” and “raw powers” of the horse. By staying in touch with our animal nature we resist full integration into the taming nature of civilization.

Capella and Diana

But the star’s history also connects Capella to the maternal. Auriga is also depicts the she-goat who nursed Zeus when he was a child, therefore exalting her to the heavens. The nurturing quality of this star is enhanced by its use in Ancient Greece. This star served as an orientation point for the temple at Eleusis dedicated to Diana, Goddess of the Moon.

Though the moon has long been associated with the body and its care, it would be specious to reduce Diana to a nurturing goddess. As the goddess of the hunt, she was able to roam freely and explore the wilderness. As a virgin goddess, her ability to move as she pleased was assured. She was not like Selene, the goddess of the full moon, or Hecate the mystic crone of the dark moon, but shows the moon in her waxing phase, incarnating into reality and embodying the heavens as something quick-footed, and powerful, yet elusive. Get too close to her, as Actaeon did, and risk being transformed into a wild animal, losing all civilizing traes. Like a horse, Artemis is not a violent being but has the power to defend her boundaries if crossed.

…

This duality is embodied in the general descriptions of this star. Brady associates Capella with a “nurturing but free-spirited flavor” and links it with the “pursuit of freedom in a non-aggressive way”. Diana does not wish to impede on the freedom of others to maintain her own; she was known for hunting with female attendants, proving her lack of restraint doesn’t impede her ability to make connections. But her love doesn’t come with caveats or obligations. “I will try hard to hold onto you with open arms,” Fiona Apple vows in “Daredevil” and Capella holds the same vibe. To be a parent is to take care of a being who will someday not need you. To love another is to continually show up and witness their shifts and changes even if they differ from what you expected.

…

How funny; I am relistening to “Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea,” ostensibly PJ Harvey’s most straightforward, hard rock, “in love,” album and I am stuck on the song that is none of that. Starting with slow piano and strings that drift through a lazy river, in bleeds Harvey’s voice, expounding a dream she had: “Horses in my dreams/Like waves, like the sea”. We don’t know if she saw them like waves in the dream or whether this is just a metaphor she added after the fact. If she really saw horses in her dreams, they must have been moving in slow motion. Though there are orchestral swells to the song, it keeps its legato, meandering tone throughout. Yet there is liberation within this molasses flow. “They pull out of here

They pull, they are free,” she tell us. In the chorus, she mimics them: “I have pulled myself clear,” she repeats like a somber chant though the relief in her voice is evident.

This song seems to depict a certain kind of freedom: one that isn’t exultant or forced like a war chant or a breaking of chains. This freedom flows in like a wave, slowly dissolving manacles or pulling you into a larger flow, one where freedom is the air you breathe. It presents freedom not as a place without work or strictures, but one where your movement is joined with something larger than you. She doesn’t explain how she pulled clear, but her feeling of doing so is undeniable, unable to be taken away.

Harvey spoke of the difficulty of writing this song because of its intimacy: “When I was writing [“Horses in my Dreams”], it was a very difficult, emotional thing to go through doing, because it is so close to me, it is a very personal song that one. And it remains so, really”.

…

Nurturing Freedom

In her Orphic Hymn, Artemis is called “Dictynna,” meaning “Lady of the Nets”. This star is not simply a star of the horse, but of the man who places a bridle atop it. We can even see Artemis’s association with childbirth as a gesture towards tethering.

To know freedom one must know chains— their weight and the lightness that comes with them falling off. But this very quality means the freedom is incomplete— relationships require our own taming, after all. A noble sacrifice, not to be weighed lightly.

Janis Joplin had Capella as her heliacal setting star. Brady sees this combination as a “struggle with a love of freedom in conflict with the need for personal commitments”— the inability to cut all ties whether they be bridle or net.

Joplin was always an outcast; she was considered unattractive in her small Texas hometown and was ostracized for her love of blues and soul music, “black” genres. She dropped out of college and moved to San Francisco to pursue music. She was known for her hard drinking and ultimately left the band that she started with to pursue a solo career. She had relationships with many men and women throughout her life and once broke a bottle over Jim Morrison’s head. But she also kept regular correspondence with her parents, even writing to them ““Weak as it is,” she wrote, “I apologize for being just so plain bad in the family,” for leaving home.

One of Janis Joplin’s most famous songs speaks to this tension. Perhaps the most famous line from “Me and Bobby McGee” is this one: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose”. Kris Kristofferson, who wrote the song, said this on inspiration for it: “The two-edged sword that freedom is. He was free when he left the girl, but it destroyed him”.

How can freedom maintain its connections? This is what Capella asks of us.

Capella natives will spend their lives trying to answer this question.

The Oracle of Delphi

The Oracle of Delphi

Introduction

Since I was young, I have been drawn to the possibility of prophecy. By “prophecy,” I gesture towards its original meaning— from the Greek prophēteia, meaning "gift of interpreting the will of the gods,"—and by gods I mean eternal laws— I mean spirit guides and daimons— I mean the 7 visible planets, and their corresponding deities— I mean the way the wind blows when you’re sitting outside and have a jolt of insight— and then you look up and the wind moves the grass towards you— there is no prescription in my focus on prophecy— work it out as anything sacred to you— anything from which you can receive a psychic message— anything outside of the small you— though we need her too.

When I was young, the mystical experiences I witnessed— certain scenes where the landscape seemed to glow— or my sense of self slipped like garlic skin— I never asked where these visions came from— regardless of my understanding I had experienced them— a sort of knowing that cannot be reasoned away.

As I got older this lack of understanding persisted— despite my best efforts at certainty. I sought to study prophecy and understand our connection to the divine beyond feelings— I tried to find the truth in the center of things— a sort of rosetta stone that could translate the essence into something I could grasp in my hand— some key for ultimate understanding myself, my world, everything in between– but each potential road to this core— writing, relationship, spirituality, divination— just led to more holes.

spirit

According to the Heart Sutra— a cornerstone Buddhist text— one of my first assays into understanding the meaning of prophecy— also known as the “Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra,”— a full name I love for its excess, imagining all the words pouring out of the mouth of its writer— The Heart Sutra is a cornerstone text in all branches of Buddhism, one I chanted every morning when I lived in a monastery— according to the sutra Avalokiteshvara— the bodhisattva of compassion— meditated and “clearly saw that all five Aggregates”— form, sensations, perceptions, mental formations, and conscious— all of them “are empty and thus relieved all suffering”—As it goes on, you see the whole chant is one of negation—“no eyes, no ear, no nose, no tongue,”—. “There is neither ignorance, nor the extinction of ignorance.”—

all dharmas are marked by emptiness;

they neither arise nor cease,

are neither defiled nor pure,

neither increase nor decrease.

Yet here I am, breathing in with my nose and watching letters fill my screen. When they are speaking of emptiness, they do not only mean void— the word my teachers gave was “potential”. Everything is shifting, particles moving, nothing staying still. Even when we have properly met the moment, unburdened by passing thoughts or mental constructs, we must remember: “You are not it but in truth it is you”. And that’s what I mean by holes— there is really no center of it all— maybe tiny centers arise and fall— but the essence of an experience is the experience itself– unable to be duplicated or clung to— then it falls away into another thing. Though we are made of this stuff, this emptiness, we cannot pin it down.

But, through engagement with emptiness, we can engage with life as it is— remember that the realization of emptiness “relieved all suffering”. In Buddhism, this form of clear seeing is called Prajna, meaning ““best knowledge,” in Sanskrit. It is often symbolized by fire, the sun, or a sword, for its startling and, at times painful, clarity— or the ability to stare at the present moment dead in its eyes— and what riches lie in that looking.

But this emptiness, this ever-shifting nature of life— gives us an entry point— a way of touching and being touched by the universe and possible changed— it gives a place for all our particularities, emotional responses, desires and details— our poetics, if you will— what moves us, coalesces into meaning or turns into a moment of deeper knowing— it says that each of these things is holy, resting in the eye of god— it says that meaning is arbitrary, just a passing aggregate that undoes itself life— there is nothing inherently meaningful about the baseball diamond I circled when I peeled back the identity of Chloe and still found a mysterious perceiver— at least nothing more meaningful than anything else— but my looking combined with its innate divinity created — giving both my inquiry and its numinosity a place to interact— creating a moment that wasn’t mine but still happened to me — with me— of me.

…

Divination

But what is the meaning behind such an event? What sort of message does it contain? What are we to do with our predictions, sights, insights?

Even then our findings are— at best— incomplete, hazy, mediated.

Prophecy, by its nature, is a game of telephone— we the humans mediate it from the gods— are not the source of it— which also adds in humility— trusting that even in prophecy you are not in charge of the message— much less its clarity or usefulness.

—imagining a connection with divinity that is completely useless— doesn’t change my life, solve my problems, make people like me more– and all the possibilities that lie beyond that— Emperor Wu asked the great teacher Bodhidharma, “What is the first principle of the holy teaching?”

Bodhidharma said, “Vast emptiness, nothing holy.”—

Thus, prophecy is, by its nature, fragmented. Take the story of the Cumaen Sibyl.

Centuries ago, concurrent with the 50th Olympiad, not long before the expulsion of Rome's kings, an old woman "who was not a native of the country"[2] arrived incognita in Rome. She offered nine books of prophecies to King Tarquin; and as the king declined to purchase them, owing to the exorbitant price she demanded, she burned three and offered the remaining six to Tarquin at the same stiff price, which he again refused, whereupon she burned three more and repeated her offer. Tarquin then relented and purchased the last three at the full original price, whereupon she "disappeared from among men".

I love that the ignorance of humans is at the core of this story. How our limited views can seem to be the source of our lack of clear seeing.

But where has this imagined wholeness ever been witnessed? This omniscience or totality?

Who, I wonder, has ever been given the complete book of their life?

There are countless stories in our canon— from Oedipus and That’s So Raven— of misunderstanding the original prediction— a seeming inevitability when we are given a shard of the whole vase– filtered through our relative interpretation— or ever-changing selves and their partial view— unable to fit the part into the whole until we live it.

Knowing the future does not necessarily change it, in other words— or guarantee our correct interpretation.

Then why do we keep trying?

.

Poetry

Perhaps because prophecy can only come to us like a piece of sea glass– a fragment, warped and smoothed by something bigger than our wills— and because the truth is always shifting— empty—unable to be confined to one outcome or definition.

I believe poetry can help us understand prophecy better.

Why is prophecy like poetry? Because what they both lack in clarity they make up for in feeling— in being lived in. Because— as I will argue here— they are by-products of connection to the ever-changing emptiness. If anything, their lack of Pure Truth is part of their power.

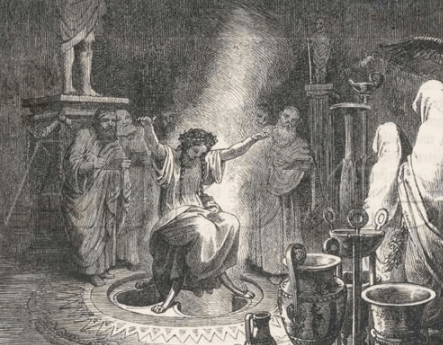

I now shift scenes to Ancient Greece. According to Rollo May, “The divinations of the priestess [at Delphi]”— living and worshipping at the Temple of Apollo, the most highly regarded and authoritative oracle between 8th and 4th century BC Greece— the prophecies of the Oracle were generally couched in poetry and were often uttered “in wild, onomatopoeic cries as well as articulate speech, and this ‘raw material’ certainly had to be interpreted and worked over”.

Interpretation of the raw experience— our participation, in other words, was required even as this participation filters and alters the original message— prophecy invites subjectivity— adulteration— which can also describe poetry— which is always more of a dream logic than a factual description of what happened.

Perhaps that is why— we are told— so few people read poetry anymore— because we read the same poets in school— Petrarch, Tennyson, Shakespeare, Eliot— and are only told the established meaning of their work instead of invited into it— when poetry is a space to be entered— explored— like a derive through the city, winding our own way— thus creating our own meaning— because poetry asks for our feelings and understanding to be created along with it— its own meaning is contingent upon our entering—it moves beyond mere entertainment and spectatorship— the predictions of the Delphic priestesses, May goes on, “were not to be received passively; the recipients had to “‘live’ themselves into the message”— enter and be changed, in other words.

True prophecy requires both the ability to connect a non-rational message to one’s subjective experience as well as the trust that your inner life’s grokking of it means something. The search for rational, objective knowledge, on the other hand, promises us a lack of ambiguity and verifiable means of testing—But this process shuts down both parties, making them inert, into things—which is useful for what science or math tries to do but not for this endeavor—“Facts don’t care about your feelings,” right?

Prophecy and art-making, on the other hand, give us a way to befriend the world. This idea reminds me of Joshua Beckman’s speech on poetry and the concept of friendship. “I feel the poem unrestrained,” Beckman describes to us in fragments, “at its core an exposure of unknowing— complex and unanswered… the freedom that is friendship...that allows the friend, unrestrained, to speak— and to be heard— not immediately designated or judged— but encountered...some ecstatic circuit’s been joined— and that’s how friendship feels”

Friendship is space. Friendship is being curious enough to drop your preconceptions— the idea that I’ve seen this baseball diamond before and that it has nothing new to offer me– that I know enough about this person to stop being present, curious— instead, to truly let the other speak. Taking after Emerson, Beckman calls friendship a “masterpiece,” but one that is “always in flux— temporary” and “can only be recognized fully from the inside”. Even someone from the inside can’t pin it down— can find no unchanging center.

This friendly encounter allows our sense of self to shift— to “a sense of self that feels outside of myself,” — which reminds me of the etymology of enthusiasm— “entheos: ‘divinely inspired, possessed by a god,’”— literally meaning “in god”— or else “ecstasy,” the altered state that allowed the priestesses their prophecy— “from ek ‘out’ (see ex-) + histanai "to place, cause to stand,"— literally to stand outside of one’s self- “but still there — right in my self,” Beckman reminds us. To become a prophet— in other words— we must open our minds around what we believe is “us”— must let the divine enter— believing we are made of the same stuff— though somehow not the same.

The process of interpreting poetry— or prophecy— of inserting ourselves into the space so generously given— can be seen as the reverse process of receiving these messages— rather than having a god enter us— “the recipients had to “live” themselves into the message,” May tells us. The poetic/prophetic act “[requires] individuals to recognize their own possibilities, enlightening new aspects of themselves and their interpersonal relationships”— it presents the possibility for change— by both merging with what is not-us– and claiming agency over how we take it in and let it shape us.

Astrology

Astrology is also like this, despite those trying to get it to answer to its lack of scientific foundation— a largely irrelevant question to me — I believe astrology is true because I have witnessed it being true again and again— the wisdom of prophecy and poetry is felt— so not quite translatable but almost impossible to take away from someone— this lack of understanding about how it works or our inability to predict how, exactly something will play out makes astrology, too, empty— and thus a worthy prophetic device— because the planets do not cause the effects we associate with its orbit— that would require them to be holes themselves— Richard Tarnas likens them to clock hands— letting us know where the universe— and by extension us, parts of the universe— currently stand.

He also describes astrological predictions as archetypal— “timeless universals that serve as the fundamental reality informing every concrete particular”— the truths of astrology predate humanity— cannot be limited to our earthly manifestation— are “dynamically indeterminate, open to inflection by many...deeply malleable, evolving” — a good astrologer will tell you a good time for love— and perhaps they will be right— but require you to ask someone out on a date or go to a bar or text a crush— for that potential to be met.

There is no guarantee of anything without our participation— we are filling the malleable archetype with our particularities— our desires and actions— and even then control is a myth— outcomes essentially unknowable and strange.

But we still need concrete objects— some sense of objectivity— against which to cast the incandescent light of our spirit joining Spirit— the Oracles of Delphi were under the purview of the God of Light– Apollo— beacon of light, clarity, conscious knowing– apparently the archaic statues of Apollo had large, dilated eyes— signs of “excessive awareness, the “looking about” on all sides lest something unknown might happen”— there must be a sense of trusting what you see, being a clear mirror or reflector of some truth.

In astrology we have the planets— in tarot, the cards— the oracles had their rituals— priming themselves for the oracular encounter— “the objective pole necessary for calling forth the subjective processes of consciousness”— remember Apollo is the father of Aesclepius— he is the sun and he is a healer— clarity can be reached, received— and does not shut off the possibility of the mystery.

Would I call my early interest in the numinous somehow prophetic? In hindsight yes— but I also want to point out its ordinariness— I simply stayed still long enough— paid attention to my experiences— how they made me feel— trusted my desires meant something— continued to invite them in—and kept doing that until I got to where I currently am. I let the world be my friend— let it enter and change me— and created my life according to what it brought me.

So know that when I say prophecy all I really mean is connection— ever-flowing, mysterious, spacious, kind— true meeting. Live by that and you are never finished, never alone, whole and complete exactly as you are.

Works Cited:

- “The Courage to Create,” Rollo May

- “The Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra”

- “Three Talks,” Joshua Beckman

- “Cosmos and Psyche,” Richard Tarnas

Since I was young, I have been drawn to the possibility of prophecy. By “prophecy,” I gesture towards its original meaning— from the Greek prophēteia, meaning "gift of interpreting the will of the gods,"—and by gods I mean eternal laws— I mean spirit guides and daimons— I mean the 7 visible planets, and their corresponding deities— I mean the way the wind blows when you’re sitting outside and have a jolt of insight— and then you look up and the wind moves the grass towards you— there is no prescription in my focus on prophecy— work it out as anything sacred to you— anything from which you can receive a psychic message— anything outside of the small you— though we need her too.

When I was young, the mystical experiences I witnessed— certain scenes where the landscape seemed to glow— or my sense of self slipped like garlic skin— I never asked where these visions came from— regardless of my understanding I had experienced them— a sort of knowing that cannot be reasoned away.

As I got older this lack of understanding persisted— despite my best efforts at certainty. I sought to study prophecy and understand our connection to the divine beyond feelings— I tried to find the truth in the center of things— a sort of rosetta stone that could translate the essence into something I could grasp in my hand— some key for ultimate understanding myself, my world, everything in between– but each potential road to this core— writing, relationship, spirituality, divination— just led to more holes.

spirit

According to the Heart Sutra— a cornerstone Buddhist text— one of my first assays into understanding the meaning of prophecy— also known as the “Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra,”— a full name I love for its excess, imagining all the words pouring out of the mouth of its writer— The Heart Sutra is a cornerstone text in all branches of Buddhism, one I chanted every morning when I lived in a monastery— according to the sutra Avalokiteshvara— the bodhisattva of compassion— meditated and “clearly saw that all five Aggregates”— form, sensations, perceptions, mental formations, and conscious— all of them “are empty and thus relieved all suffering”—As it goes on, you see the whole chant is one of negation—“no eyes, no ear, no nose, no tongue,”—. “There is neither ignorance, nor the extinction of ignorance.”—

all dharmas are marked by emptiness;

they neither arise nor cease,

are neither defiled nor pure,

neither increase nor decrease.

Yet here I am, breathing in with my nose and watching letters fill my screen. When they are speaking of emptiness, they do not only mean void— the word my teachers gave was “potential”. Everything is shifting, particles moving, nothing staying still. Even when we have properly met the moment, unburdened by passing thoughts or mental constructs, we must remember: “You are not it but in truth it is you”. And that’s what I mean by holes— there is really no center of it all— maybe tiny centers arise and fall— but the essence of an experience is the experience itself– unable to be duplicated or clung to— then it falls away into another thing. Though we are made of this stuff, this emptiness, we cannot pin it down.

But, through engagement with emptiness, we can engage with life as it is— remember that the realization of emptiness “relieved all suffering”. In Buddhism, this form of clear seeing is called Prajna, meaning ““best knowledge,” in Sanskrit. It is often symbolized by fire, the sun, or a sword, for its startling and, at times painful, clarity— or the ability to stare at the present moment dead in its eyes— and what riches lie in that looking.

But this emptiness, this ever-shifting nature of life— gives us an entry point— a way of touching and being touched by the universe and possible changed— it gives a place for all our particularities, emotional responses, desires and details— our poetics, if you will— what moves us, coalesces into meaning or turns into a moment of deeper knowing— it says that each of these things is holy, resting in the eye of god— it says that meaning is arbitrary, just a passing aggregate that undoes itself life— there is nothing inherently meaningful about the baseball diamond I circled when I peeled back the identity of Chloe and still found a mysterious perceiver— at least nothing more meaningful than anything else— but my looking combined with its innate divinity created — giving both my inquiry and its numinosity a place to interact— creating a moment that wasn’t mine but still happened to me — with me— of me.

…

Divination

But what is the meaning behind such an event? What sort of message does it contain? What are we to do with our predictions, sights, insights?

Even then our findings are— at best— incomplete, hazy, mediated.

Prophecy, by its nature, is a game of telephone— we the humans mediate it from the gods— are not the source of it— which also adds in humility— trusting that even in prophecy you are not in charge of the message— much less its clarity or usefulness.

—imagining a connection with divinity that is completely useless— doesn’t change my life, solve my problems, make people like me more– and all the possibilities that lie beyond that— Emperor Wu asked the great teacher Bodhidharma, “What is the first principle of the holy teaching?”

Bodhidharma said, “Vast emptiness, nothing holy.”—

Thus, prophecy is, by its nature, fragmented. Take the story of the Cumaen Sibyl.

Centuries ago, concurrent with the 50th Olympiad, not long before the expulsion of Rome's kings, an old woman "who was not a native of the country"[2] arrived incognita in Rome. She offered nine books of prophecies to King Tarquin; and as the king declined to purchase them, owing to the exorbitant price she demanded, she burned three and offered the remaining six to Tarquin at the same stiff price, which he again refused, whereupon she burned three more and repeated her offer. Tarquin then relented and purchased the last three at the full original price, whereupon she "disappeared from among men".

I love that the ignorance of humans is at the core of this story. How our limited views can seem to be the source of our lack of clear seeing.

But where has this imagined wholeness ever been witnessed? This omniscience or totality?

Who, I wonder, has ever been given the complete book of their life?

There are countless stories in our canon— from Oedipus and That’s So Raven— of misunderstanding the original prediction— a seeming inevitability when we are given a shard of the whole vase– filtered through our relative interpretation— or ever-changing selves and their partial view— unable to fit the part into the whole until we live it.

Knowing the future does not necessarily change it, in other words— or guarantee our correct interpretation.

Then why do we keep trying?

.

Poetry

Perhaps because prophecy can only come to us like a piece of sea glass– a fragment, warped and smoothed by something bigger than our wills— and because the truth is always shifting— empty—unable to be confined to one outcome or definition.

I believe poetry can help us understand prophecy better.

Why is prophecy like poetry? Because what they both lack in clarity they make up for in feeling— in being lived in. Because— as I will argue here— they are by-products of connection to the ever-changing emptiness. If anything, their lack of Pure Truth is part of their power.

I now shift scenes to Ancient Greece. According to Rollo May, “The divinations of the priestess [at Delphi]”— living and worshipping at the Temple of Apollo, the most highly regarded and authoritative oracle between 8th and 4th century BC Greece— the prophecies of the Oracle were generally couched in poetry and were often uttered “in wild, onomatopoeic cries as well as articulate speech, and this ‘raw material’ certainly had to be interpreted and worked over”.

Interpretation of the raw experience— our participation, in other words, was required even as this participation filters and alters the original message— prophecy invites subjectivity— adulteration— which can also describe poetry— which is always more of a dream logic than a factual description of what happened.

Perhaps that is why— we are told— so few people read poetry anymore— because we read the same poets in school— Petrarch, Tennyson, Shakespeare, Eliot— and are only told the established meaning of their work instead of invited into it— when poetry is a space to be entered— explored— like a derive through the city, winding our own way— thus creating our own meaning— because poetry asks for our feelings and understanding to be created along with it— its own meaning is contingent upon our entering—it moves beyond mere entertainment and spectatorship— the predictions of the Delphic priestesses, May goes on, “were not to be received passively; the recipients had to “‘live’ themselves into the message”— enter and be changed, in other words.

True prophecy requires both the ability to connect a non-rational message to one’s subjective experience as well as the trust that your inner life’s grokking of it means something. The search for rational, objective knowledge, on the other hand, promises us a lack of ambiguity and verifiable means of testing—But this process shuts down both parties, making them inert, into things—which is useful for what science or math tries to do but not for this endeavor—“Facts don’t care about your feelings,” right?

Prophecy and art-making, on the other hand, give us a way to befriend the world. This idea reminds me of Joshua Beckman’s speech on poetry and the concept of friendship. “I feel the poem unrestrained,” Beckman describes to us in fragments, “at its core an exposure of unknowing— complex and unanswered… the freedom that is friendship...that allows the friend, unrestrained, to speak— and to be heard— not immediately designated or judged— but encountered...some ecstatic circuit’s been joined— and that’s how friendship feels”

Friendship is space. Friendship is being curious enough to drop your preconceptions— the idea that I’ve seen this baseball diamond before and that it has nothing new to offer me– that I know enough about this person to stop being present, curious— instead, to truly let the other speak. Taking after Emerson, Beckman calls friendship a “masterpiece,” but one that is “always in flux— temporary” and “can only be recognized fully from the inside”. Even someone from the inside can’t pin it down— can find no unchanging center.

This friendly encounter allows our sense of self to shift— to “a sense of self that feels outside of myself,” — which reminds me of the etymology of enthusiasm— “entheos: ‘divinely inspired, possessed by a god,’”— literally meaning “in god”— or else “ecstasy,” the altered state that allowed the priestesses their prophecy— “from ek ‘out’ (see ex-) + histanai "to place, cause to stand,"— literally to stand outside of one’s self- “but still there — right in my self,” Beckman reminds us. To become a prophet— in other words— we must open our minds around what we believe is “us”— must let the divine enter— believing we are made of the same stuff— though somehow not the same.

The process of interpreting poetry— or prophecy— of inserting ourselves into the space so generously given— can be seen as the reverse process of receiving these messages— rather than having a god enter us— “the recipients had to “live” themselves into the message,” May tells us. The poetic/prophetic act “[requires] individuals to recognize their own possibilities, enlightening new aspects of themselves and their interpersonal relationships”— it presents the possibility for change— by both merging with what is not-us– and claiming agency over how we take it in and let it shape us.

Astrology

Astrology is also like this, despite those trying to get it to answer to its lack of scientific foundation— a largely irrelevant question to me — I believe astrology is true because I have witnessed it being true again and again— the wisdom of prophecy and poetry is felt— so not quite translatable but almost impossible to take away from someone— this lack of understanding about how it works or our inability to predict how, exactly something will play out makes astrology, too, empty— and thus a worthy prophetic device— because the planets do not cause the effects we associate with its orbit— that would require them to be holes themselves— Richard Tarnas likens them to clock hands— letting us know where the universe— and by extension us, parts of the universe— currently stand.

He also describes astrological predictions as archetypal— “timeless universals that serve as the fundamental reality informing every concrete particular”— the truths of astrology predate humanity— cannot be limited to our earthly manifestation— are “dynamically indeterminate, open to inflection by many...deeply malleable, evolving” — a good astrologer will tell you a good time for love— and perhaps they will be right— but require you to ask someone out on a date or go to a bar or text a crush— for that potential to be met.

There is no guarantee of anything without our participation— we are filling the malleable archetype with our particularities— our desires and actions— and even then control is a myth— outcomes essentially unknowable and strange.

But we still need concrete objects— some sense of objectivity— against which to cast the incandescent light of our spirit joining Spirit— the Oracles of Delphi were under the purview of the God of Light– Apollo— beacon of light, clarity, conscious knowing– apparently the archaic statues of Apollo had large, dilated eyes— signs of “excessive awareness, the “looking about” on all sides lest something unknown might happen”— there must be a sense of trusting what you see, being a clear mirror or reflector of some truth.

In astrology we have the planets— in tarot, the cards— the oracles had their rituals— priming themselves for the oracular encounter— “the objective pole necessary for calling forth the subjective processes of consciousness”— remember Apollo is the father of Aesclepius— he is the sun and he is a healer— clarity can be reached, received— and does not shut off the possibility of the mystery.

Would I call my early interest in the numinous somehow prophetic? In hindsight yes— but I also want to point out its ordinariness— I simply stayed still long enough— paid attention to my experiences— how they made me feel— trusted my desires meant something— continued to invite them in—and kept doing that until I got to where I currently am. I let the world be my friend— let it enter and change me— and created my life according to what it brought me.

So know that when I say prophecy all I really mean is connection— ever-flowing, mysterious, spacious, kind— true meeting. Live by that and you are never finished, never alone, whole and complete exactly as you are.

Works Cited:

- “The Courage to Create,” Rollo May

- “The Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra”

- “Three Talks,” Joshua Beckman

- “Cosmos and Psyche,” Richard Tarnas